The cold call came as Leah Jameson was sipping coffee in her Vancouver garden. Five years earlier, she’d felt a lump during a routine self-exam – a moment that spiraled into a whirlwind of mammograms, biopsies, and eventually, surgery for her hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

“My oncologist was calling to tell me about a new drug approval,” Leah told me when we met at a local cancer support center. “After everything I went through – the surgery, radiation, years of hormone therapy – all I could think was how this could have changed my journey.”

What her doctor was referring to was Health Canada’s recent approval of ribociclib (Kisqali) as an adjuvant treatment for adults with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HR+/HER2-) early breast cancer at high risk of recurrence. This approval marks a significant shift in how early-stage breast cancer might be treated across Canada.

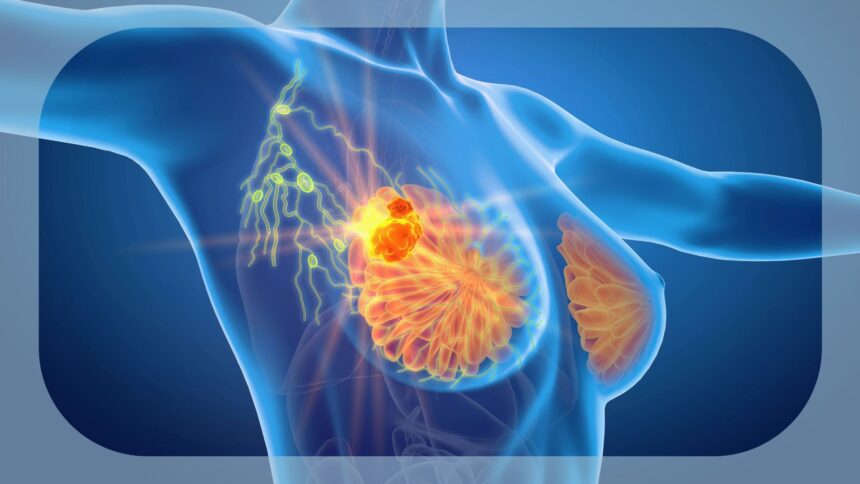

Ribociclib belongs to a class of medications called CDK4/6 inhibitors that work by blocking proteins crucial for cell division. While these inhibitors have been used for metastatic breast cancer, their application in early-stage disease represents an evolution in treatment strategy.

Dr. Karen Martinez, a medical oncologist at BC Cancer, explains the significance: “Previously, many early-stage breast cancer patients received hormone therapy alone after surgery. Now we have evidence that adding ribociclib can reduce recurrence risk by approximately 25% in high-risk patients. That’s potentially hundreds of recurrences prevented across Canada annually.”

The approval stems from the NATALEE trial, which followed over 5,000 patients with stage II and III HR+/HER2- breast cancer. Results showed significantly improved invasive disease-free survival among patients receiving ribociclib alongside hormone therapy compared to hormone therapy alone.

Behind clinical trial data are stories like Mariam Abdi’s. The 42-year-old elementary school teacher from Surrey was diagnosed last year with stage III breast cancer. “My children were 8 and 10 when I was diagnosed,” she shared while we walked along the seawall near False Creek. “Every decision I’ve made about treatment has been with them in mind. Reducing my chance of recurrence isn’t just a statistic – it’s about being there to see them grow up.”

For patients like Mariam, the timing of this approval demonstrates how quickly cancer treatment is evolving. When she completed chemotherapy and surgery three months ago, ribociclib wasn’t an option for early-stage disease. Now her oncology team is discussing whether she might benefit from adding it to her hormone therapy regimen.

However, questions about access remain. Innovative cancer medications often face a gap between regulatory approval and public coverage across provinces. Breast cancer advocate Sandra Mitchell from the Canadian Breast Cancer Network points out this disconnect.

“Health Canada approval is just the first step,” Mitchell emphasized during our phone conversation. “Now we need provincial formularies to make coverage decisions. Without that, many patients face either significant out-of-pocket costs or simply go without.”

Cost barriers are particularly concerning for Indigenous communities and remote populations. In northern British Columbia, where I’ve reported on healthcare access challenges, patients sometimes travel hundreds of kilometers for specialized cancer care. Adding expensive medications without coverage creates another layer of inequity in an already strained system.

Novartis, the company behind ribociclib, reports they’re working with pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance to negotiate pricing that would facilitate public coverage. Meanwhile, some private insurers have already begun covering the treatment for early-stage disease.

Dr. Sandeep Gill, a medical oncologist who works with underserved communities in East Vancouver, expressed cautious optimism when we spoke at a recent medical conference. “This approval gives us another tool against one of the most common cancers affecting Canadian women. But that tool is only valuable if patients can actually access it.”

The science behind ribociclib represents a growing trend toward targeted therapies that may help reduce reliance on chemotherapy for some patients. Traditional chemotherapy affects all rapidly dividing cells – both cancerous and healthy – leading to familiar side effects like hair loss and severe nausea. CDK4/6 inhibitors more specifically target cancer cell mechanisms.

This doesn’t mean ribociclib is without side effects. Common reactions include fatigue, nausea, and decreased white blood cell counts that require regular monitoring. Less commonly, it can affect liver function and heart rhythm.

“We’re getting better at managing these side effects,” notes nurse practitioner Joanne Chen, who coordinates breast cancer care at a downtown clinic. “Most patients find them more manageable than traditional chemotherapy, though monitoring is crucial.”

For patients like Emily Wong, a 51-year-old Vancouver Island resident diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer last year, the approval brings hope. “After my diagnosis, I joined online support groups and learned about this treatment being used in clinical trials. I wondered if I would ever have access. Now it might be an option for me.”

As Canadian provinces consider coverage for adjuvant ribociclib, patients and advocates emphasize that time matters. Unlike some health decisions that can wait for policy processes, cancer treatment windows are time-sensitive.

“Every month matters when you’re trying to prevent recurrence,” Dr. Martinez explained. “Patients diagnosed today need answers about coverage soon, not years from now.”

The approval of ribociclib for early breast cancer represents a meaningful advance in Canadian oncology care. For patients like Leah, Mariam, and Emily, it offers new hope in the fight against one of Canada’s most common cancers. But that hope must be matched with equitable access across geographic and socioeconomic boundaries if it’s to fulfill its promise.

As Canada navigates this new treatment landscape, the voices of patients themselves must remain central to the conversation – not just in clinical decisions, but in the policy choices that determine who benefits from medical innovation.