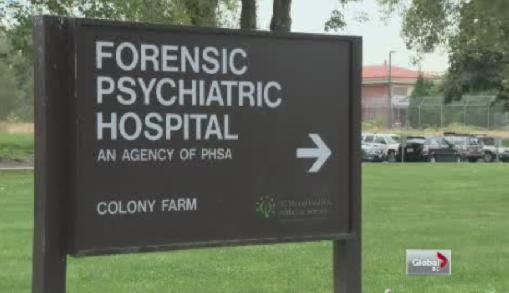

As the morning fog lifts over the grounds of the Forensic Psychiatric Hospital in Coquitlam, staff members shuffle through security checkpoints, preparing for another day inside British Columbia’s only secure facility for mentally ill offenders. The 190-bed hospital—known locally as “Colony Farm”—has operated beyond capacity for years, creating what frontline workers describe as a pressure cooker environment affecting both patient care and staff safety.

“Some days, we’re making decisions about who gets admitted based not on clinical need, but on available space,” explains Dr. Vijay Singh, a psychiatrist who has worked at the facility for eight years. “It means people who should be receiving specialized treatment are instead waiting in correctional facilities or emergency rooms across the province.”

The hospital houses individuals found not criminally responsible for offenses due to mental disorders, as well as those deemed unfit to stand trial. With BC’s population growing and the mental health crisis deepening, advocates and healthcare professionals are increasingly calling for the construction of a second forensic psychiatric facility.

Last week, I visited the aging facility where hallways designed decades ago now serve a patient population with increasingly complex needs. Nurses described working double shifts as staffing shortages persist, creating conditions where therapeutic programs are sometimes canceled due to safety concerns.

Melissa Chan, a psychiatric nurse at Colony Farm for eleven years, pulled me aside during my tour. “We’re not just talking about building another facility for more beds,” she said, lowering her voice. “We need modern spaces designed for recovery—places where people can heal without feeling like they’re in a prison.”

Data from the BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services shows the average wait time for admission to the hospital has increased by 37% since 2018. During the same period, workplace injury claims from staff have risen by 28%, according to WorkSafeBC statistics.

The provincial government has acknowledged these challenges. Health Minister Adrian Dix recently told reporters that “the ministry is exploring options for expanding forensic psychiatric services,” though no concrete timeline or budget has been announced.

For families of patients, the overcrowded conditions mean fewer opportunities for meaningful rehabilitation. Sarah Patterson’s brother has been at Colony Farm for three years following a psychotic episode that led to assault charges. She drives from Kelowna every month to visit him.

“He shares a small room with another patient who triggers his anxiety,” Patterson told me over coffee near the facility. “The staff try their best, but they’re stretched too thin. Sometimes therapy sessions get canceled because there aren’t enough clinicians available.”

The BC Government and Service Employees’ Union (BCGEU), which represents many of the facility’s workers, has been advocating for a second hospital for years. According to their recent report, nearly 60% of forensic psychiatric patients come from regions outside the Lower Mainland, creating additional barriers for family support—a crucial element in successful rehabilitation.

Dr. Rakesh Lamba, clinical director at the BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services, believes a second facility would ideally be located in the province’s Interior. “We know from research that maintaining family connections improves outcomes,” Dr. Lamba explained. “Having patients housed hundreds of kilometers from their support networks creates another obstacle to recovery.”

The Forensic Psychiatric Hospital itself dates back to 1997, though parts of the facility are older. The aging infrastructure presents additional challenges, from outdated security systems to spaces that weren’t designed for modern therapeutic approaches.

Mental health advocates point to models in Ontario and Quebec, where multiple forensic facilities serve different regions and levels of security needs. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto recently opened a state-of-the-art forensic building that emphasizes both security and healing environments—a stark contrast to BC’s aging facility.

Walking the grounds at Colony Farm, I noticed the strain on everyone’s faces—from the security personnel at the entrance to the clinical staff hurrying between units. The weight of responsibility in a perpetually overcrowded environment is palpable.

Darlene McLeod has visited her son at the hospital every week for four years. “When he first arrived, there were art programs, music therapy, regular counseling,” she said. “Now half the time these programs are canceled because they’re short-staffed or dealing with incidents elsewhere in the building.”

The BC Schizophrenia Society has joined calls for expanded forensic psychiatric services. Their executive director, Faydra Aldridge, emphasized that inadequate facilities create a revolving door effect. “Without proper treatment environments, we see higher rates of relapse when patients return to the community,” Aldridge said.

Experts estimate that BC needs at least 80 additional forensic psychiatric beds to meet current demand, with projections suggesting that number could double within a decade as the province’s population grows.

For now, the staff at Colony Farm continue doing their best with limited resources. As I left the facility, a recreational therapist was setting up for a small group session in a repurposed storage room—making do with what they have while hoping decision-makers will soon recognize the urgent need for expanded services.

“We’re not just warehousing people here,” Dr. Singh reminded me as I departed. “These are individuals who deserve proper care and the chance to recover. But we need the resources to provide that care effectively.”

Until then, British Columbia’s only forensic psychiatric hospital continues operating beyond capacity, a situation that many fear is compromising both care and safety for some of the province’s most vulnerable patients.