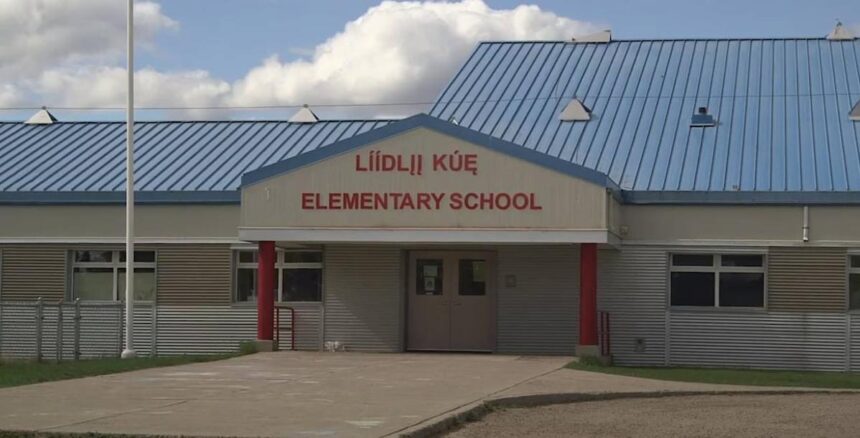

As the orange haze of sunset stretches across Fort Simpson, the community gathering at Líídlįį Kúę Elementary School tells a story far beyond a typical parent-teacher meeting. Tempers flare, voices rise, and a palpable frustration echoes through the gym where nearly 60 parents have assembled.

“We’ve been asking questions for months and getting nowhere,” says Jennifer Simmons, mother of two elementary students, her voice trembling slightly. “Our children deserve better than this constant uncertainty.“

The source of this tension? The unexpected removal of school principal Meghan Schnurr in early September, a decision that has fractured trust between parents and education authorities in this small Northwest Territories community of about 1,200 residents.

Fort Simpson’s education troubles reflect a deeper struggle facing many northern communities – balancing local governance with territorial oversight while maintaining educational stability for students who already face unique challenges.

Parents claim they received no explanation when Schnurr was suddenly replaced just days into the new school year. The Dehcho Divisional Education Council (DDEC), which oversees schools in the region, has remained tight-lipped about specific reasons, citing privacy concerns and personnel confidentiality.

“It feels like we’re being treated as if we don’t deserve answers,” explains Matthew Grossman, whose children have attended the school for four years. “This isn’t just about one principal – it’s about transparency and respecting our community’s right to understand decisions that impact our kids.”

The situation has rapidly evolved from a staffing change into something more significant. According to territorial education records, Fort Simpson schools have experienced higher-than-average principal turnover rates, with five different administrators in the past seven years – nearly double the territorial average for communities of similar size.

Education experts warn such instability can have lasting effects. Dr. Sarah McCrimmon, an education policy researcher at Lakehead University who studies northern school systems, notes that “consistency in leadership is particularly crucial in small, remote communities where schools serve as social anchors. Frequent changes can destabilize not just educational outcomes but community cohesion.”

The parents’ frustration boiled over last Tuesday when they delivered a petition with 215 signatures – representing nearly a fifth of the community’s population – to DDEC offices in Fort Providence. The petition demands three specific actions: a formal explanation for Schnurr’s removal, community involvement in selecting the next principal, and the establishment of a parent advisory committee with meaningful input on school governance.

What makes this situation particularly complex is the intersection of educational governance and Indigenous self-determination. The DDEC operates within a framework that aims to incorporate Dene values and perspectives, with four of seven board members representing Indigenous communities.

Sarah Hardisty-Catholique, a Dene elder who has grandchildren in the school, offers a nuanced perspective: “Our people have fought hard for control over our children’s education. But with that comes responsibility to the whole community. When decisions happen behind closed doors, it brings back bad memories of times when decisions about our children were made without our input.”

The DDEC has responded with a statement acknowledging parents’ concerns while maintaining its position on confidentiality. “We understand the community’s desire for information,” wrote Superintendent Rebecca Jessen. “While we cannot discuss personnel matters publicly, we remain committed to providing a stable, supportive learning environment for students.”

This response has done little to quell frustration. At the most recent community meeting, several parents proposed more dramatic action, including withdrawing children from school for a day of protest. Others suggested appealing directly to the territorial Minister of Education.

The controversy occurs against a backdrop of challenging educational metrics in the region. According to the NWT Bureau of Statistics, graduation rates in the Dehcho region have hovered around 56% over the past five years, compared to 67% territory-wide. Parents and some educators quietly suggest that leadership instability contributes to these outcomes.

Acting principal Thomas Whitaker, brought in from Yellowknife to temporarily lead the school, faces a daunting task. “My focus is entirely on providing stability for students during this transition,” he told parents at the meeting. “Your children’s education remains our top priority.”

For students, the situation creates uncertainty. Twelve-year-old Kaylee Cli-Michaud expressed it simply: “I liked Ms. Schnurr. She knew everyone’s name and came to our basketball games. Now we have someone new again, and I don’t know if they’ll stay.”

As winter approaches in Fort Simpson, where temperatures will soon plunge below -30°C, the community faces a chill that extends beyond the weather. Without resolution, parents warn that trust – once broken – becomes harder to rebuild with each passing school day.

“We’re not going anywhere,” says Jennifer Simmons as parents gather their coats and prepare to head home. “This is our community, these are our children, and we’ll keep pushing until we get the transparency we deserve.”

For now, students continue attending classes while adults grapple with questions of governance, transparency, and what it really means for a community to have a voice in its children’s education.