The scent hits you first. Sweet, earthy, with an undercurrent of something deeper—the smell of transformation. Standing at the edge of the Sea to Sky Composting Facility near Squamish, I watch as a front-end loader turns a massive pile of what was, just weeks ago, the discarded remains of thousands of meals from Metro Vancouver.

“This isn’t garbage,” says Jaye-Jay Berggren, the facility’s operations manager, gesturing to mountains of decomposing food scraps. “This is climate action happening right before your eyes.”

He’s not exaggerating. According to recent research from Simon Fraser University, diverting food waste from landfills to composting and biogas facilities could offset greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to removing 1.3 million cars from Canadian roads annually.

The numbers are staggering. Each year, Canadians waste approximately 2.3 million tonnes of edible food. When this organic matter decomposes in landfills, it produces methane—a greenhouse gas 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide at trapping heat in our atmosphere.

But while food waste is a significant climate problem, it’s also an opportunity hiding in plain sight.

Last month, I visited three innovative waste diversion projects across British Columbia that are turning this environmental liability into a climate asset. What I found was a patchwork of solutions—some high-tech, others remarkably simple—that together offer a path toward meaningful emissions reduction.

At the Richmond Biogas Facility, engineer Sarah Nguyen shows me how food waste becomes energy. “We’re essentially accelerating a natural process,” she explains as we tour the anaerobic digestion facility. Sealed tanks break down food waste in an oxygen-free environment, capturing the methane that would otherwise escape into the atmosphere.

“That captured biogas displaces natural gas in the grid,” Nguyen says. “One tonne of food waste processed here creates enough energy to heat a home for nearly three weeks while preventing the equivalent of 70 kilograms of CO₂ from entering the atmosphere.”

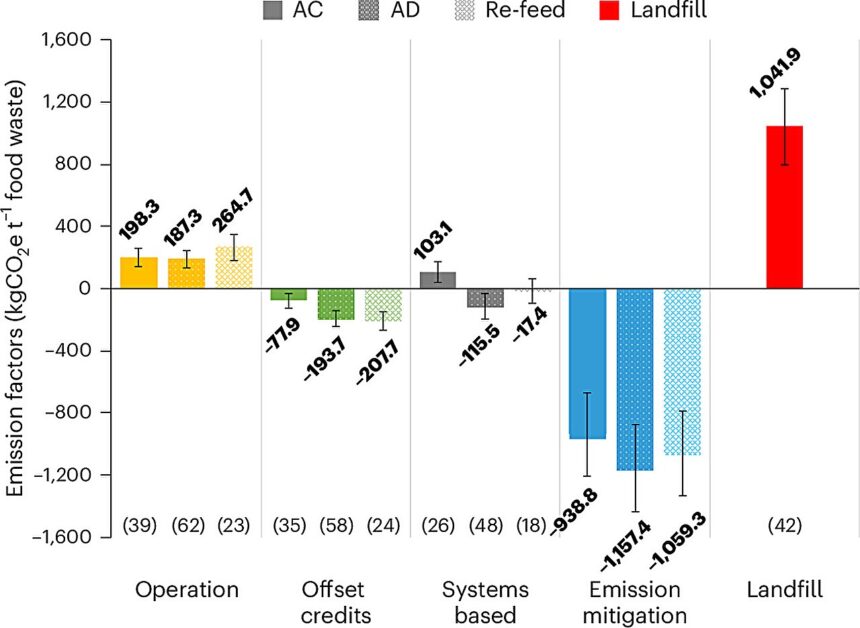

The process isn’t perfect. Transportation emissions and operational energy use mean these facilities still have a carbon footprint. But according to research published in Environmental Science & Technology, even accounting for these factors, food waste recycling reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 60-70% compared to landfilling.

The climate benefits extend beyond methane capture. The finished compost replaces synthetic fertilizers on farms and gardens throughout the region. Since these fertilizers are typically produced using natural gas, each kilogram of compost represents another small victory in emissions reduction.

At UBC Farm, I meet Dr. Hannah Wilson, who studies the carbon sequestration potential of compost-amended soils. Walking through test plots, she points out the visible difference between treated and untreated sections.

“Adding compost improves soil structure and increases its carbon storage capacity,” Wilson explains. “Our preliminary findings suggest that high-quality compost application can sequester between 0.5 and 2 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent per hectare annually.”

Yet despite these benefits, the Environment and Climate Change Canada reports that over 50% of Canadian food waste still ends up in landfills. The barriers are both structural and behavioral.

In Powell River, a coastal community of 13,000, I meet with members of the Food Waste Reduction Coalition. Their grassroots approach tackles the problem at its source—prevention rather than treatment.

“Large-scale composting is crucial, but we also need to waste less food to begin with,” says coalition founder Elena Markova. The group has created a community fridge network where restaurants and grocers can donate food that would otherwise be discarded.

Their efforts illustrate an important principle: the climate impact of food waste happens across its entire lifecycle. The emissions from producing, processing, packaging, and transporting food that ultimately goes uneaten represent a massive climate burden. According to a recent World Wildlife Fund report, if global food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases after China and the United States.

Back at the Sea to Sky facility, Berggren is optimistic but realistic about the challenges ahead. “We’ve doubled our processing capacity in the last five years, but we’re still catching up to the volume of organic waste generated in this region.”

Infrastructure limitations remain a significant obstacle. Many rural communities lack access to composting facilities, and even in urban areas, contamination from non-compostable items reduces efficiency and increases costs.

The federal government has recognized this opportunity. Last year, Environment and Climate Change Canada announced $150 million in funding for organic waste diversion infrastructure as part of its 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan. Provincial programs like CleanBC have set targets to reduce organic waste disposal by 95% by 2030.

But experts warn that regulations alone won’t solve the problem. “We need better packaging labeling, expanded processing infrastructure, and widespread behavior change,” says Dr. Thomas Chen of the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions.

For Indigenous communities like the Líl̓wat Nation, whose traditional territory includes part of the Sea to Sky corridor, food waste recycling connects to deeper cultural values. “Our ancestors understood that nothing should be wasted,” says cultural advisor Theresa Williams. “The modern composting movement is catching up to what Indigenous peoples have practiced for generations—returning food to the earth in ways that nurture future growth.”

As the climate crisis intensifies, these connections between waste management and emissions reduction will only grow more important. While headline-grabbing technologies like direct air capture receive significant attention, the humble compost pile represents an immediately available climate solution.

Standing amid the steam rising from decomposing food at the Sea to Sky facility, I’m struck by the poetry of the process—yesterday’s waste becoming tomorrow’s soil. It’s a small but meaningful climate victory happening in communities across Canada, one apple core and coffee ground at a time.

As I leave, Berggren hands me a bag of finished compost. “Plant something,” he says with a smile. “It’s good for the soul and the planet.”