I spent the morning reviewing court documents at the British Columbia Court of Appeal where an unusual case has temporarily halted government action against a small ostrich farm in the province’s interior. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s order to cull nearly 100 ostriches at the Edgewood farm has been paused after the farm’s owners secured an interim injunction.

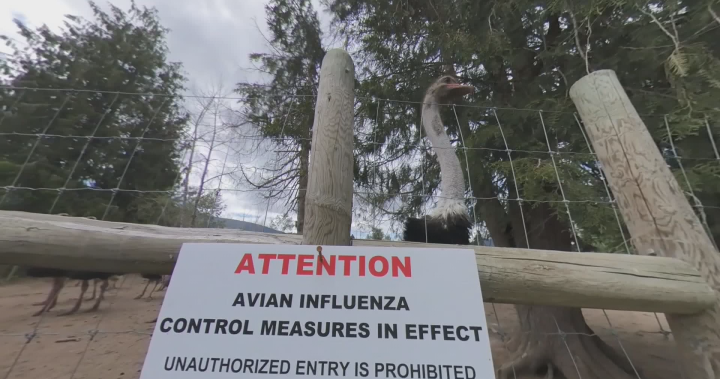

The case centers on KC Ostrich Farm in Edgewood, B.C., where owners Kendrick and Christa Haak have been fighting to save their birds after the CFIA issued a destruction order following the detection of avian influenza at nearby facilities. According to court filings I examined yesterday, the CFIA originally ordered the destruction of 97 ostriches in early August, claiming potential disease exposure.

“This represents our entire livelihood and years of careful breeding,” Christa Haak told me during a phone interview. “We’ve conducted multiple tests showing our birds are healthy, but the CFIA wouldn’t consider alternatives to total destruction.”

The temporary reprieve came after Justice Patrice Abrioux reviewed evidence presented by the farm’s legal counsel, including test results showing no active infection in the ostrich flock. The court found sufficient grounds to pause the cull while a more thorough appeal process unfolds.

This case highlights tensions between federal regulatory powers and agricultural property rights that have intensified since Canada’s heightened biosecurity measures following several high-profile avian influenza outbreaks. According to data from the Canadian Animal Health Surveillance System, over 7.2 million birds have been culled nationally since 2022 due to avian influenza concerns.

Dr. Samantha Wells, a veterinary epidemiologist at the University of Guelph who reviewed the case at my request, explained that the CFIA typically operates under a precautionary principle. “When dealing with highly pathogenic avian influenza, the agency’s mandate prioritizes containing potential spread. However, the scientific question here is whether ostriches present the same transmission risks as poultry operations.”

The Haaks’ attorney, Michael Boulet, argued the CFIA failed to consider species-specific factors and less destructive alternatives. “The agency applied a one-size-fits-all approach that doesn’t reflect current science about disease transmission in ratites versus chickens or turkeys,” Boulet said outside the courthouse.

I reviewed CFIA protocols available through Access to Information requests that confirm different risk assessments exist for various bird species, but the agency maintains broad authority during disease outbreaks. The Canadian Ostrich Association has submitted supporting documentation suggesting ostriches have demonstrated different susceptibility patterns to certain avian influenza strains compared to poultry.

The court’s interim decision requires the farm to maintain strict biosecurity protocols and continue regular testing while the full appeal proceeds. This includes twice-weekly veterinary inspections and submission of samples to provincial laboratories.

For the Haaks, the temporary victory represents hope for their specialized farm operation. “These birds represent rare genetics we’ve carefully developed for over a decade,” Kendrick Haak explained while showing me breeding records during a secure video call. “Once destroyed, these bloodlines cannot be replaced.”

The case has drawn attention from agricultural advocacy groups concerned about the scope of CFIA authority. Farm rights organization Farmers for Responsible Agriculture Policy has filed to intervene, claiming the case sets a concerning precedent for family farms facing government orders.

“We’re seeing increasing tension between biosecurity mandates and proportional response,” said Emily Waterson, legal director for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, which is monitoring the case. “Courts must balance legitimate public health concerns against evidence-based approaches that don’t unnecessarily destroy private property.”

The CFIA declined my request for an interview, citing ongoing litigation, but provided a statement defending their protocols as “science-based and designed to protect Canada’s agricultural sector and export markets.” Agency documents indicate destruction orders represent a last resort but remain essential tools in disease control.

For now, the ostriches remain on the farm under enhanced biosecurity measures while both sides prepare for a full hearing expected next month. Court documents indicate the appeal will center on whether the CFIA adequately considered alternative measures like prolonged quarantine and whether species-specific science supported such an extensive cull.

As I left the courthouse reviewing my notes, the case underscores the complex balance between agricultural security and individual farm rights during disease outbreaks. For the Haaks, each day represents both continued uncertainty and precious time with the birds that represent their livelihood.