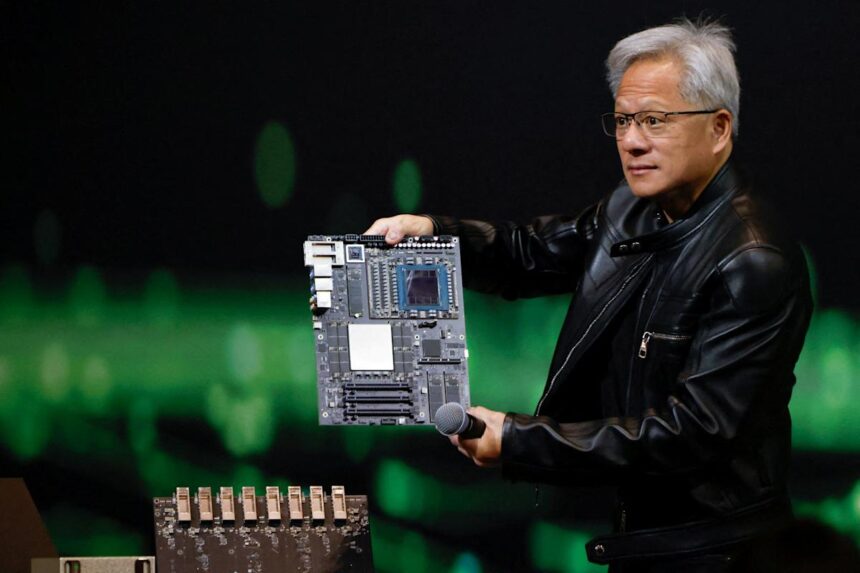

The morning I spent with three AI startup founders last month in Toronto’s MaRS Discovery District revealed something peculiar: each carried the same rectangular piece of hardware in their development labs. These weren’t just any components, but Nvidia’s H100 graphics processing units—each costing upwards of $30,000 and collectively forming the backbone of their artificial intelligence ambitions.

“Without these,” admitted Sanjay Mitthal, whose computer vision startup has raised $17 million, “we’d basically be stuck in the research phase for another year.”

This scene isn’t unique to Canada. Across the global technology landscape, a striking pattern has emerged: Nvidia has transformed from a gaming hardware manufacturer into the essential infrastructure provider powering a staggering $306 billion AI startup ecosystem.

The numbers tell a compelling story. Since OpenAI released ChatGPT in late 2022, venture capital has flooded into AI startups at an unprecedented rate. According to PitchBook data, AI startups raised over $68 billion in 2023 alone—with another $42 billion in the first half of 2024. But unlike previous tech booms where software dominated, today’s AI revolution has a decidedly hardware-dependent foundation.

“The relationship between AI startups and Nvidia isn’t just important—it’s existential,” explains Ming Zhao, partner at Radical Ventures in an interview. “When we evaluate potential investments, access to computational resources is now among our top three criteria, alongside team quality and market opportunity.”

The dependency runs deep. Anthropic, a leading AI research company that competes with OpenAI, reportedly spends approximately $500,000 daily on computing resources—much of it flowing to Nvidia-powered cloud services. Claude, their flagship AI assistant, required roughly 5,000 Nvidia GPUs for training according to industry estimates.

For startups without billion-dollar funding rounds, this creates both opportunity and vulnerability. Access to computing has become the modern equivalent of prime real estate in the gold rush era.

The Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, which manages over $570 billion in assets, has noticed this shift. “We’re seeing an infrastructure layer emerging around AI computation,” notes Leon Pedersen, managing director of venture investments at CPPIB. “Startups that can efficiently utilize these resources have an inherent advantage in this market.”

This dynamic has created several interesting ripple effects across the innovation ecosystem:

Cloud computing giants like AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure have bolstered their Nvidia GPU offerings, often with specialized packages for AI startups. Microsoft’s investment in OpenAI gave the startup privileged access to Azure’s Nvidia-powered infrastructure.

A secondary market for computational resources has emerged. Startups like Lambda Labs and CoreWeave have built businesses solely around providing access to Nvidia hardware, with the latter reaching a $7 billion valuation primarily by being nimbler than larger cloud providers in deploying Nvidia chips.

Venture capital firms increasingly offer GPU credits alongside funding. Sequoia Capital, Andreessen Horowitz, and others now provide portfolio companies with millions in computing credits—recognizing that code alone isn’t enough.

The Bank of Canada’s analysis of tech investment patterns shows computational infrastructure now represents between 18-24% of early-stage AI companies’ burn rates—a dramatic increase from just 6% in 2019.

Yet Nvidia’s dominance creates vulnerability. When a single company’s products become so essential to an entire industry, challenges inevitably arise. Recent quarterly results showed Nvidia capturing approximately 80% of the AI chip market, with competitors like AMD and Intel struggling to gain meaningful traction.

“The concentration risk is real,” warns Patricia Thaine, co-founder of Private AI, whose data privacy technology relies on Nvidia’s computing architecture. “When we faced chip delays last year, we had to postpone a major product launch by three months. There simply weren’t viable alternatives.”

Supply chain constraints have eased somewhat in 2024, but the fundamental dependence remains. Nvidia has leveraged this position to create an expanding ecosystem of software, tools, and platforms. Their CUDA programming framework has become the de facto standard for AI development—further entrenching their position.

The economic impact extends beyond startups. Ontario’s Invest Ontario reports that regions offering reliable access to AI computing infrastructure are winning the battle for technology investment. Toronto’s innovation corridor has seen a 38% increase in AI company formations in areas with dedicated high-performance computing facilities.

“It’s not just about the chips,” explains Rohan Nair, who leads AI strategy at Royal Bank of Canada. “It’s about the entire stack of technology that Nvidia has built. The development environments, the optimization tools, the pre-trained models—these create powerful network effects that are difficult to replicate.”

This relationship between Nvidia and the AI startup ecosystem represents a fascinating economic symbiosis. The chipmaker reported $26 billion in data center revenue last quarter alone, largely driven by AI applications. Meanwhile, startups dependent on these chips have collectively raised hundreds of billions in venture funding.

For investors and founders, understanding this dynamic is crucial. The most successful AI startups aren’t merely developing novel algorithms—they’re mastering the efficient use of computational resources. Companies like Cohere and Stability AI have distinguished themselves by achieving impressive results with relatively modest computing budgets.

The Canadian AI ecosystem has adapted by developing specialized expertise in computational efficiency. The Vector Institute in Toronto has launched programs specifically focused on helping startups optimize their AI workloads for Nvidia hardware.

Looking ahead, several forces may reshape this landscape. New chip designs from competitors, specialized AI accelerators, and even quantum computing loom on the horizon as potential disruptors. Startups exploring alternative approaches to machine learning that require less computational power are attracting increasing attention.

“The most interesting companies we’re seeing today are finding ways to deliver AI value without requiring massive GPU clusters,” notes Michelle Scarborough of BDC Capital’s Women in Technology Venture Fund. “They’re using techniques like synthetic data, transfer learning, and edge computing to sidestep some of the hardware dependencies.”

The $306 billion question facing the AI industry is whether Nvidia’s central role represents a transitional phase or a durable economic structure. The answer will shape not just technology development, but investment patterns across the innovation economy for years to come.

For now, those rectangular processors humming away in startup labs across Toronto and beyond remain the heartbeat of an AI revolution still in its early stages. The gold rush continues—with Nvidia selling the picks and shovels that everyone seems to need.