Filed from Saskatoon

The thunderous downpour last July that left parts of Saskatoon underwater wasn’t just another prairie storm. For residents like Marion Laberge, whose Churchill Drive basement filled with knee-deep water, it was a painful reminder of the city’s vulnerability.

“Everything was destroyed – family photos, furniture, my son’s hockey memorabilia,” Laberge told me during a community meeting last week. “The city promised solutions after the 2017 floods. We’re still waiting.”

That wait may soon be ending. Saskatoon’s ambitious flood mitigation strategy, first developed after devastating floods in 2017, has reached a critical milestone with several major projects nearing completion this spring.

The $54-million initiative, which combines infrastructure upgrades with natural water management systems, represents the city’s most comprehensive approach to flood prevention in decades.

“We’re working against time and changing weather patterns,” explained Angela Gardiner, Saskatoon’s General Manager of Utilities and Environment. “What used to be called hundred-year storms are happening every five to seven years now.”

Gardiner’s assessment aligns with Environment Canada data showing a 12% increase in extreme precipitation events across the Saskatchewan River basin over the past decade.

The Montgomery Place neighborhood has been first to see tangible results. The area’s new $8.3-million underground stormwater system, designed to handle water volumes 40% greater than previous infrastructure, is now 85% complete according to city engineers.

“Montgomery residents have suffered through three major floods since 2015,” noted Ward 2 Councillor Hilary Gough during our phone conversation. “This project isn’t just about infrastructure – it’s about giving people peace of mind during our increasingly violent summer storms.”

For Churchill-Riversdale resident Thomas Blackburn, that peace of mind can’t come soon enough. His home has flooded twice in five years.

“Every time it rains heavily, we’re all watching the street gutters, wondering if this is the storm that breaks through again,” Blackburn said, pointing to water marks still visible on his basement walls.

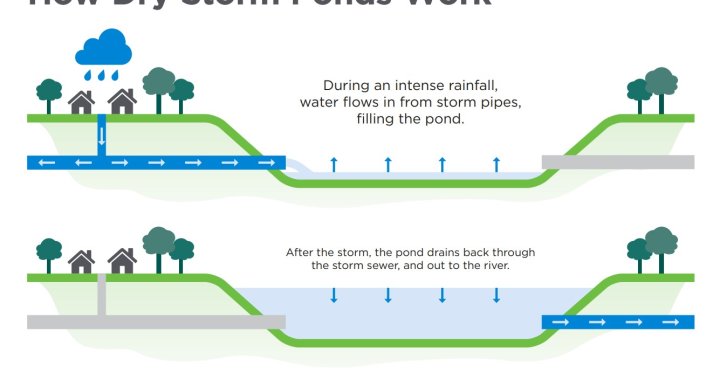

The most visible component of the city’s strategy sits at W.W. Ashley Park, where a $12-million dry pond system capable of temporarily holding enough stormwater to fill six Olympic swimming pools is nearly operational. During normal conditions, the area functions as recreation space – a dual-purpose design increasingly adopted across Canadian municipalities.

“The dry pond approach represents smart planning,” explained Dr. Kerry Mazurek, civil engineering professor at the University of Saskatchewan. “It maximizes limited urban space while providing crucial overflow capacity during extreme weather events.”

Less visible but equally important are upgrades to the city’s nine lift stations, critical infrastructure that moves wastewater during flood events. Six stations have received complete overhauls with improved pumping capacity and backup power systems.

The progress comes none too soon for business owners in Saskatoon’s flood-prone areas. Cheryl Woloschuk, whose River Landing boutique suffered $30,000 in uninsured damages during last summer’s flooding, remains cautiously optimistic.

“The city keeps talking about these projects, but last July proved we’re still vulnerable,” Woloschuk said. “I’ve installed my own flood barriers, but ultimately we need the city’s systems to work.”

City documents show the remaining projects are scheduled for completion by late 2025, with the Montgomery and Churchill-Riversdale neighborhoods prioritized based on historical flood frequency and severity.

The strategy also includes less traditional approaches. Saskatoon’s “Green Streets” initiative has planted over 120 rain gardens throughout the city, each designed to absorb and filter thousands of liters of stormwater before it reaches storm sewers.

“These natural systems provide multiple benefits beyond flood mitigation,” said Robin Majorki, urban sustainability coordinator with the Meewasin Valley Authority. “They filter pollutants, support urban biodiversity, and beautify neighborhoods – all while reducing pressure on our aging infrastructure.”

But challenges remain. Internal city reports obtained through freedom of information requests reveal that infrastructure in older neighborhoods like Nutana and Buena Vista will require an additional $18 million in upgrades beyond current budget allocations.

Saskatoon’s flood strategy also exists within a broader provincial context. The Saskatchewan Water Security Agency has identified urban flooding as a growing concern across the province, with Saskatoon, Regina and Prince Albert all experiencing significant flood events since 2017.

“Municipal infrastructure designed in the 1960s and 70s simply wasn’t built for today’s weather patterns,” noted Susan Ross, the agency’s director of watershed planning. “Cities across Saskatchewan are playing catch-up.”

The province has contributed $14.8 million to Saskatoon’s flood mitigation efforts through the Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program, with the federal government adding another $18.3 million.

For residents like Marion Laberge, the completion of these projects represents more than infrastructure improvements – it’s about restoring confidence in a city they love.

“We chose Saskatoon because it felt safe, stable,” she said, watching city crews work on a storm sewer across from her home. “When you’ve been flooded multiple times, you start questioning everything – should we stay, should we go somewhere less risky?”

As Saskatchewan faces increasingly unpredictable weather patterns, Saskatoon’s approach may become a template for other prairie communities. The integration of traditional engineering with green infrastructure offers a blueprint for flood resilience that balances immediate protection with long-term sustainability.

City officials have scheduled community information sessions throughout April and May to update residents on project timelines and discuss emergency preparations for the upcoming storm season.

The question remaining for many Saskatoon residents isn’t whether these projects will help – it’s whether they’ll be completed before the next major storm tests the city’s defenses once again.