The soft hum of the clinic room feels different now. Dr. Maya Chopra no longer stares at her computer screen while patients describe their symptoms. Instead, she makes eye contact, listens intently, and occasionally glances at a tablet where an AI assistant silently transcribes and organizes the conversation.

“Before, I was typing frantically while trying to listen,” Dr. Chopra tells me as we sit in her Vancouver clinic. “Patients would joke that I was more interested in my computer than them. It wasn’t true, but perception matters in healthcare.”

We’re witnessing a quiet revolution in British Columbia’s healthcare system. AI-powered tools are transforming how frontline providers deliver care—not by replacing human judgment, but by handling administrative burdens that have long pulled clinicians away from meaningful patient interactions.

At the Surrey Memorial Hospital emergency department, Dr. James Wong demonstrates their new diagnostic support system. A 67-year-old patient with chest pain has arrived. As Wong examines him, the AI reviews the patient’s history, vital signs, and ECG results, then suggests three possible diagnoses ranked by probability.

“It’s not making the decisions,” Wong emphasizes. “But it helps ensure I don’t miss something crucial when we’re overwhelmed with patients. Last month, it flagged a rare aortic dissection that might have been initially misdiagnosed as heartburn during our busiest hour.”

According to a recent study from the BC Centre for Health Innovation, clinics using these AI assistants have reduced diagnostic delays by 31% and administrative documentation time by nearly 40%. These aren’t just efficiency metrics—they represent critical minutes returned to patient care.

The Provincial Health Services Authority began piloting these systems in 2022 at three hospitals. Today, they’re implemented in over 30 facilities across the province, with plans to expand to rural and remote communities by next year.

“We’ve seen particularly promising results in remote Indigenous communities,” says Dr. Rebecca Cardinal, who oversees the Northern Health implementation. “When you combine AI tools with telehealth, practitioners in isolated communities can provide care that previously required patients to travel hundreds of kilometers.”

At Dzawada’enuxw First Nation’s health center on Kingcome Inlet, nurse practitioner Sarah Wilson shows me how the AI helps bridge gaps in specialist access. When faced with unusual symptoms, the system helps identify potential conditions that warrant immediate evacuation versus those that can be managed locally.

“Last winter, a young man came in with what looked like a simple infection, but the system flagged warning signs of necrotizing fasciitis based on subtle presentation patterns,” Wilson recounts. “We arranged emergency transport immediately. The surgeon later told us that delay would have likely meant amputation.”

These successes don’t mean implementation has been seamless. Privacy advocates have raised concerns about patient data security, especially given that some of these technologies are developed by American companies not subject to Canadian privacy laws.

“We’ve insisted on data sovereignty,” explains Michael Chen, BC’s Deputy Minister of Health Technology. “All patient information remains on Canadian servers, and we’ve negotiated contracts that explicitly prevent using BC patient data to train commercial AI models.”

Healthcare workers have had mixed reactions. A survey by the BC Nurses’ Union found that 62% of nurses reported positive experiences with the new tools, while 23% expressed concerns about reliability and training time. The remaining 15% were neutral or unsure.

“The technology is only as good as the implementation,” says Sonia Brar, a registered nurse at Vancouver General Hospital. “When we’re short-staffed and overwhelmed, learning new systems feels like another burden. But where it’s been rolled out with proper training and support, it’s making a real difference.”

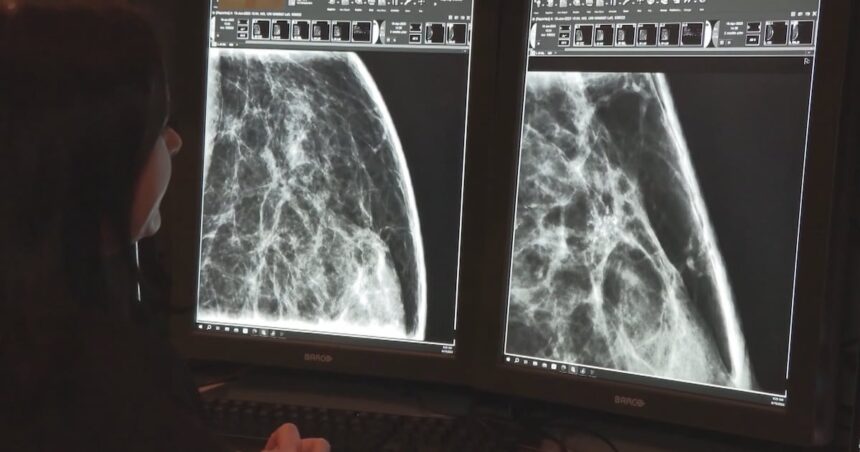

Perhaps the most promising applications are in preventive care. At Burnaby’s Edmonds Community Health Centre, an AI system reviews patient records overnight, identifying those due for cancer screenings, vaccinations, or chronic disease follow-ups.

“It caught 18 patients who had fallen through the cracks for colon cancer screening in our first month,” says Dr. Farhad Mehdipour, the clinic’s medical director. “Two had early-stage cancer detected. That’s potentially two lives saved because an algorithm noticed what we missed during our hectic days.”

Cost remains a significant concern. The provincial implementation represents a $45 million investment over five years. Critics question whether these funds could better serve the system by hiring more staff instead.

However, preliminary data from the Ministry of Health suggests the technology may eventually pay for itself through reduced hospital readmissions, faster diagnoses, and more efficient use of specialist time.

“It’s not an either/or proposition,” argues Dr. Bonnie Henry, BC’s Provincial Health Officer. “We need both more healthcare workers and smarter systems that help those workers practice at the top of their licenses.”

As my day of observations ends, I return to Dr. Chopra’s clinic for her final thoughts. She points to a waiting room that, while still busy, moves more efficiently than before.

“The technology isn’t perfect,” she admits. “But for the first time in years, I leave work having given my patients my full attention rather than dividing it with paperwork. That alone makes this worthwhile.”

For patients across British Columbia, this shift represents a return to something that should never have been lost in modern healthcare—the healing power of being truly seen and heard by your care provider, with technology enabling rather than interfering with that fundamental human connection.