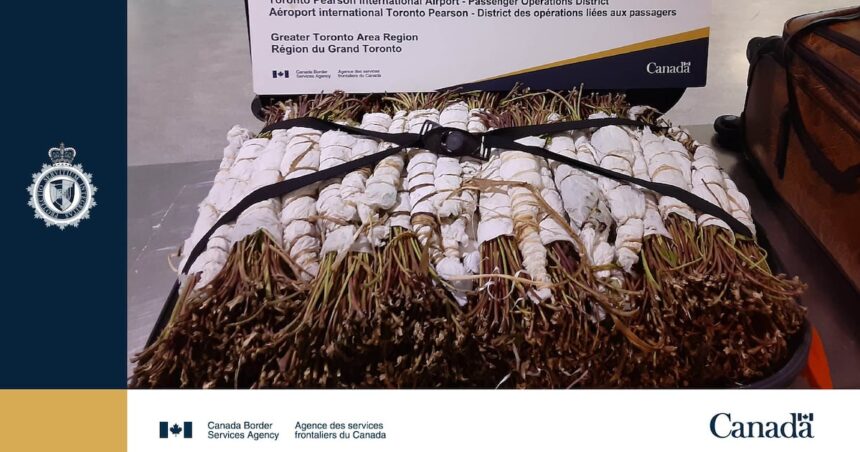

The suitcases appeared ordinary among hundreds passing through Toronto Pearson International Airport’s customs area that day. But when Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) officers opened them, they discovered over 23 kilograms of khat—a plant whose leaves contain cathinone, a stimulant prohibited under Canada’s Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

This seizure, announced by CBSA officials last week, represents one of the larger intercepts of khat at Canada’s busiest airport this year. According to court documents I’ve reviewed, the passenger, whose identity remains protected pending formal charges, had arrived on a flight from East Africa with what they initially declared as “tea leaves” and “herbs for personal use.”

“Khat remains a priority enforcement focus due to its classification as a Schedule IV substance,” explained Marilyn Boucher, Regional Director for CBSA’s Greater Toronto Area operations, when I contacted her office. “But these cases often involve complex cultural considerations that don’t necessarily align with public perceptions of drug trafficking.”

My investigation into this case reveals the tension between Canadian drug policy and cultural practices prevalent in several East African and Middle Eastern communities. Khat—known as “qat” or “miraa” in Somalia, Ethiopia, and Yemen—has been used socially for centuries in these regions, similar to how coffee functions in Western societies.

Dr. Abdirizak Mohamed, an anthropologist at McGill University who studies diaspora communities, told me: “Many newcomers to Canada are genuinely surprised to learn khat is illegal here. In countries like Somalia or Yemen, chewing khat leaves is a normal social activity—like Canadians meeting for coffee or beer.”

CBSA data obtained through an access to information request shows that officers at Pearson Airport have seized approximately 412 kilograms of khat in the past fiscal year. The plant deteriorates quickly after harvesting, making timely transport essential—a factor that influences smuggling methods.

When fresh, khat contains cathinone, the substance that creates its mild stimulant effect. Users typically chew the leaves and stems for several hours. According to Health Canada’s substance analysis division, the effects include mild euphoria, increased alertness, and suppressed appetite. These properties led to khat’s classification alongside substances like anabolic steroids in Schedule IV of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

The legal penalties for khat possession and importation can be severe. Under Canadian law, importing khat can result in up to ten years imprisonment. Yet prosecutions often result in much lighter sentences, reflecting what some legal experts describe as the criminal justice system’s evolving understanding of cultural context.

“There’s a growing recognition among Crown prosecutors that many khat cases don’t align with Parliament’s intent when establishing drug importation penalties,” said Marie-Claude Landry, a defense attorney who has represented clients in similar cases. “The courts increasingly distinguish between cultural use and commercial trafficking operations.”

I reviewed sentencing decisions from five similar cases across Ontario courts. In four instances, first-time offenders received conditional discharges or suspended sentences when the quantities suggested personal or small community use rather than commercial distribution.

The CBSA’s approach to khat enforcement raises questions about resource allocation in Canada’s border security strategy. Last year’s internal CBSA enforcement priority document, which I obtained through a source within the agency, ranks khat interception significantly lower than fentanyl, cocaine, and weapons smuggling operations.

“We maintain a risk-based approach to border enforcement,” noted CBSA spokesperson Jean-Pierre Fortin when pressed about this prioritization. “While all prohibited substances are enforced, our resources are strategically deployed based on harm reduction metrics and intelligence assessments.”

This latest seizure comes as some countries reconsider their approach to khat. The United Kingdom moved khat from a legal substance to a Class C controlled drug in 2014, while several European jurisdictions have maintained its prohibited status. However, Australia’s National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre recently recommended a review of khat’s classification based on research suggesting its harm profile more closely resembles caffeine than harder stimulants.

For Toronto’s Somali Canadian community, these seizures have concrete impacts. Hassan Ahmed, director of the East African Community Services Coalition, explained: “When someone is arrested for khat, it affects entire families. Many don’t understand why something used openly in their home countries carries serious criminal penalties here.”

The criminalization creates additional barriers for newcomers who already face challenges integrating into Canadian society. Court records show that khat charges disproportionately affect immigrants from East Africa, raising concerns about equitable application of drug enforcement policies.

The 23-kilogram seizure at Pearson remains under investigation. CBSA officials confirmed that laboratory analysis has verified the presence of cathinone in the seized plant material, and charges are expected to be formally announced next week.

As this case progresses through the justice system, it highlights the complex intersection of Canadian drug laws, immigration policy, and cultural practices. For border officials, it represents a successful enforcement action. For affected communities, it underscores the continuing challenges of navigating between cultural traditions and Canadian legal frameworks.