The morning light filters through the windows of Kingston General Hospital’s waiting room where Ellen Samuels clutches a paper cup of lukewarm coffee. Her husband Mike was admitted three days ago with what they initially thought was a severe case of pneumonia. “The fever came on so fast,” she tells me, her voice barely audible above the hospital’s ambient noise. “By night, he couldn’t catch his breath.”

Mike is one of dozens fighting Legionnaires’ disease in what Ontario public health officials are now calling the province’s largest outbreak in recent memory. As of this week, 43 people have been infected, and one person has died. The outbreak, centered in Kingston, has transformed routine summer activities into potential health hazards as investigators race to identify the source.

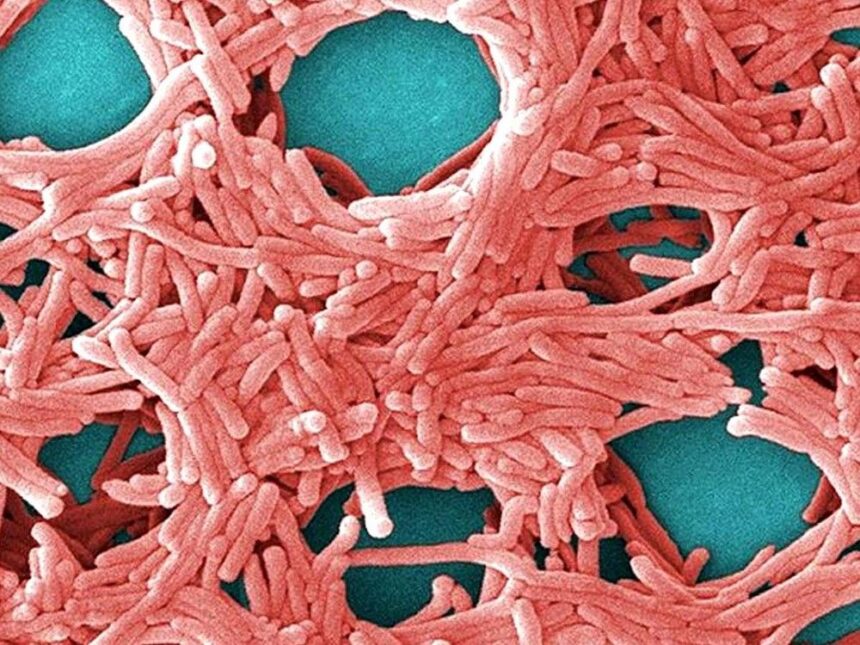

Legionnaires’ disease—a severe form of pneumonia caused by Legionella bacteria—spreads not through person-to-person contact but through microscopic water droplets. The bacteria thrive in warm water systems like cooling towers, decorative fountains, hot tubs, and complex plumbing networks. When people inhale contaminated aerosols, the bacteria can settle deep in the lungs, triggering an infection that mimics pneumonia but can rapidly intensify.

“What makes this particularly challenging is that Legionnaires’ often affects the most vulnerable among us,” explains Dr. Kieran Moore, Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health, whom I reached by phone as he coordinated the provincial response. “The elderly, smokers, those with weakened immune systems—they face the highest risk.” Moore confirms that many of the current cases involve adults over 65, though the infection has appeared across various age groups.

Walking through downtown Kingston with local resident James Chen, he points to various air conditioning units humming above storefronts. “It’s surreal to think something that keeps us comfortable could make us sick,” he says. Chen’s neighbor was among those hospitalized last week. “You don’t think about the invisible risks in everyday life until something like this happens.”

Public Health Ontario has deployed environmental health officers to test cooling towers, fountains, and other potential sources throughout the region. The painstaking process involves collecting water samples, culturing the bacteria (which can take days), and then matching the environmental strain to patient samples.

Dr. Linna Li, an infectious disease specialist at Queen’s University, explains why identifying the source is so critical: “Legionella outbreaks don’t resolve on their own. The contaminated water source continues exposing people until it’s properly treated.” Li notes that even after the source is identified, decontamination requires specialized cleaning and potentially long-term monitoring.

At Kingston’s waterfront, yellow caution tape surrounds a decorative fountain that normally draws children on hot summer days. It’s one of several water features temporarily shut down as a precaution. Public health officials have also advised businesses with cooling towers to conduct emergency disinfection while the investigation continues.

For those already infected, the road to recovery can be difficult. Legionnaires’ disease typically requires hospitalization and extended antibiotic treatment. Respiratory support is often necessary, and in severe cases, patients may need intensive care.

Back at Kingston General, I meet Dr. Samira Mukherjee as she finishes her rounds. “What’s frustrating about Legionnaires’ is that it’s entirely preventable with proper water management,” she says. “Yet when outbreaks occur, they can be devastating.” The hospital has added extra staff to handle the influx of patients with respiratory symptoms, many arriving anxious after hearing news reports.

Ontario’s health system has faced similar challenges before. In 2005, a Toronto outbreak infected 135 people and claimed 21 lives. That incident led to stricter regulations for cooling towers and water systems in many buildings. However, compliance and enforcement remain ongoing challenges, according to Public Health Ontario’s latest assessment report on waterborne disease prevention.

The human toll extends beyond physical symptoms. “There’s a psychological impact to environmental outbreaks like this,” says community health worker Diane Williams, who’s been helping affected families navigate the healthcare system. “People wonder if their everyday environments are safe. That anxiety doesn’t disappear quickly.”

Provincial health authorities have established a dedicated hotline for residents concerned about potential exposure. They advise anyone experiencing symptoms—particularly fever, cough, shortness of breath, muscle aches, and headaches—to seek medical attention immediately and mention possible Legionnaires’ exposure.

For Ellen Samuels and others with loved ones in treatment, each day brings cautious hope. “The doctors say Mike is responding to the antibiotics,” she says, relief evident in her tired eyes. “But then I think about the family of the person who didn’t make it, and it just breaks my heart.”

As evening approaches, Kingston settles into an uneasy quiet. Restaurant patios that would typically be filled remain partially empty. At the public library, a hastily organized information session draws a crowd of concerned residents. Public health nurses patiently answer questions, emphasizing that the municipal water supply remains safe for drinking and bathing.

This outbreak serves as a stark reminder of how environmental health directly impacts community wellbeing. As climate change drives warmer temperatures across Canada, health experts at the National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health warn that conditions favorable to Legionella growth may increase, potentially making vigilant water system maintenance even more crucial in coming years.

As Ontario health officials continue their investigation, communities across the province watch closely, reminded once again of the delicate balance between the built environment and public health—and how quickly that balance can be disrupted when invisible threats find their way into the air we breathe.