The phone rang at 4:30 AM. As a journalist, early calls usually signal breaking news, but this one was different. My cousin Emily was calling from the hospital in Kelowna, her voice thin with exhaustion. “The doctors think it’s salmonella,” she said. “From that charcuterie board at our family reunion.”

Emily wasn’t alone. Across Canada, a quiet crisis has been unfolding this summer as more Canadians find themselves battling severe food poisoning linked to contaminated salami products. According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, two more people were hospitalized this week, bringing the total hospitalization count to eleven, while twelve new illnesses have been identified since last week’s update.

“We’re seeing a concerning pattern of cases concentrated in British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario,” explains Dr. Mira Patel, an infectious disease specialist at Vancouver General Hospital. “Most patients report consuming Italian-style dry-cured meats within seven days before falling ill.”

The outbreak, which began in May 2025, has now affected 64 Canadians across five provinces. Health Canada has linked the cases to several brands of Italian-style salamis produced at a facility in southern Ontario. What started as isolated reports has grown into one of the most significant foodborne illness outbreaks in recent years.

When I visited Emily in hospital the next day, the ward housed three other patients with similar symptoms. A nurse told me they’d seen a steady stream of cases over the past month—many requiring IV fluids and close monitoring for dehydration.

“The symptoms hit me like a freight train,” Emily recalls, still connected to an IV drip. “Fever, cramps that felt like my insides were being wrung out, and the worst headache of my life. I thought it was just a stomach bug at first.”

Salmonella bacteria cause approximately 87,500 illnesses annually in Canada, according to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). But this particular strain—Salmonella Typhimurium—appears particularly virulent. The hospitalization rate for this outbreak stands at 17%, higher than the typical 11% seen in most salmonella outbreaks.

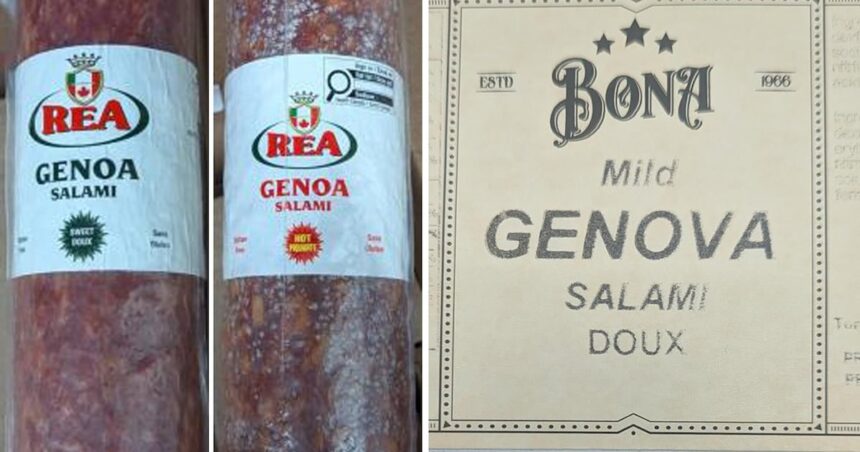

The CFIA has issued recalls for seven brands of salami products so far, but epidemiologists believe more contaminated products may still be circulating. The investigation has revealed that the affected salamis share a common supplier of raw ingredients, though officials haven’t yet pinpointed the exact source of contamination.

“This is a particularly challenging investigation,” says Marie Cloutier, a CFIA food safety specialist I spoke with yesterday. “Dry-cured meats have a long shelf life, so contaminated products may remain in people’s refrigerators for months. And consumers often transfer these products from original packaging to serving boards, making it harder to trace exposure.”

This outbreak reflects broader challenges in our food safety systems. Dr. Sylvia Richardson, professor of food microbiology at the University of British Columbia, explains that increasingly complex supply chains make tracing contamination more difficult than ever.

“Twenty years ago, your salami might contain ingredients from two or three sources,” she tells me as we walk through her lab where researchers test food samples. “Today’s products might include components from dozens of suppliers across multiple countries. One contaminated ingredient can affect numerous end products.”

For vulnerable populations, these outbreaks pose serious risks. Children under five, pregnant women, older adults, and those with compromised immune systems face higher chances of severe illness. Of the 64 confirmed cases in this outbreak, nine have been children under ten.

Jennifer Martinez, a Toronto mother whose seven-year-old daughter was hospitalized for three days with salmonella poisoning, describes the experience as terrifying. “She became so dehydrated so quickly. The doctors said if we’d waited even a day longer to bring her in, it could have been much worse.”

The economic impact extends beyond medical costs. Martinez missed a week of work caring for her daughter. “There’s no paid family leave at my job. Between lost wages and hospital parking, this has cost us over $1,000—all because someone didn’t properly clean equipment or test ingredients.”

The CFIA has inspected the production facility identified as the likely source, though they haven’t released their findings publicly. According to internal documents obtained through information request, the facility had previously been cited for sanitation violations in early 2024, though those issues were reportedly addressed.

Health Canada recommends consumers check their refrigerators for the recalled products, which include brands distributed nationally through major supermarket chains. Even if the salami looks and smells normal, the bacteria may still be present. Anyone experiencing symptoms—including fever, chills, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, headache, nausea, or vomiting—should seek medical attention and mention possible salami consumption.

As Emily recovers, she’s become vigilant about food safety. “I used to just glance at best-before dates. Now I research every recall, check internal cooking temperatures, and avoid cross-contamination like my life depends on it—because it might.”

This outbreak serves as a reminder that our food system, despite advances in safety protocols, remains vulnerable. As we increasingly embrace artisanal foods and global ingredients, the pathways for contamination multiply. Regulatory agencies continue working to adapt, but consumers must remain informed and cautious.

For my cousin and the dozens of other Canadians affected, this summer will be remembered not for planned adventures but for unexpected hospital stays. As Emily puts it, “You never think it’ll happen to you until suddenly, it does.”