When law enforcement becomes the focus of a courtroom, the fundamental question of who polices the police takes center stage. Last Friday, this question echoed through a Toronto courtroom as Constable Calvin Au, a seven-year veteran of the Toronto Police Service, received a 12-month conditional sentence for the assault of a 19-year-old during what should have been a routine Kijiji transaction.

The sentence allows Au to avoid jail time, instead serving his punishment under house arrest for the first six months, followed by a curfew for the remaining period. Justice Paul Burstein also ordered 100 hours of community service and two years of probation.

“This sentence must send a message that the public’s trust in police cannot be violated without serious consequences,” Justice Burstein stated during the hearing. I observed Au’s face remain stoic as the judge emphasized the gravity of abusing police authority.

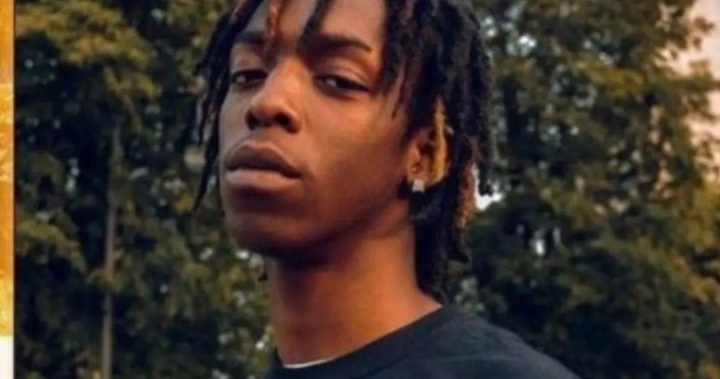

The case stems from a February 2022 incident when Au, off-duty but identifying himself as a police officer, met the young man who was selling basketball shoes on Kijiji. According to court documents I reviewed, Au accused the seller of offering counterfeit merchandise, then physically assaulted him, causing injuries that required hospital treatment.

Crown prosecutor Mabel Lai had sought a jail term of 6-8 months, arguing that “when an officer breaks the law they are sworn to uphold, it tears at the fabric of public confidence.” The prosecution presented evidence that Au had displayed his badge before the assault, deliberately invoking his authority to intimidate.

Defense lawyer Gary Clewley painted a different picture, describing Au as an officer with an otherwise unblemished record who “made a terrible mistake in a moment of poor judgment.” Clewley provided the court with character references from Au’s colleagues and community members.

The victim, whose identity is protected by a publication ban, provided a powerful impact statement. “I used to believe police were there to protect people like me. Now I feel anxiety whenever I see an officer,” he told the court. The young man described ongoing psychological trauma and fear of meeting strangers for online transactions.

The case highlights the complicated relationship between police accountability and public trust. Cheryl Mahyr, spokesperson for the Office of the Independent Police Review Director, told me that complaints against officers have increased 27% over the past three years. “Public scrutiny of police conduct has intensified,” Mahyr explained, “particularly when officers invoke their authority in off-duty situations.”

Toronto Police Association president Jon Reid acknowledged the damage such incidents cause. “The actions of one officer can undermine the dedicated work of thousands,” Reid said in a statement. “We respect the court’s decision and recognize that accountability applies to everyone who wears the badge.”

The Toronto Police Service confirmed that Au remains suspended with pay, as required under Ontario’s Police Services Act. A separate disciplinary hearing will determine his future with the force.

Criminal lawyer Daniel Brown, who was not involved in the case but specializes in police accountability, explained that conditional sentences for officers are increasingly common. “Courts are recognizing that incarceration isn’t always necessary for deterrence,” Brown said. “The loss of career and public standing often constitutes significant punishment itself.”

The case has renewed calls for reform to Ontario’s police oversight system. The Canadian Civil Liberties Association has long advocated for changes to the Police Services Act, particularly the provision that allows officers to remain on payroll while suspended.

“When citizens see officers avoiding jail time for conduct that would likely imprison a civilian, it creates a perception of a two-tiered justice system,” said Abby Deshman, director of the Criminal Justice Program at the CCLA. “Meaningful accountability must be transparent and consistent.”

For the victim and his family, the sentence represents partial closure to a traumatic chapter. His mother, speaking briefly outside the courthouse, expressed mixed feelings. “We’re relieved this is over, but no sentence can undo what happened to my son,” she said. “We just want him to feel safe again.”

As Au left the courtroom flanked by supporters, a small group of police accountability activists held signs reading “Badge ≠ Immunity.” The case may soon fade from headlines, but it leaves behind important questions about power, accountability, and the complex relationship between those who enforce the law and those who depend on them for protection.

The next step in this saga will be Au’s disciplinary hearing, which could result in dismissal from the force. For Toronto residents who follow such cases closely, the outcome will serve as yet another measure of whether justice truly applies equally to everyone—even those who wear a badge.