I stood in front of the memorial wall at the SOLID Outreach Society in Victoria, scanning the hundreds of photos. Each smiling face represents someone lost to British Columbia’s toxic drug crisis – sons, daughters, friends, neighbors. In the corner, staff member Mikayla was adding three new photos from the past week.

“We’re running out of wall space,” she told me quietly.

This somber reality gained statistical weight when the BC Coroners Service released their April report. Last month, at least 189 British Columbians died from toxic drugs – averaging more than six deaths every day. On Vancouver Island alone, 34 lives were lost, representing a 21% increase from April 2023.

Since BC declared a public health emergency in 2016, over 14,000 people have died from toxic drugs. Behind each number is a story – a life cut short, a family forever changed.

“What makes this crisis particularly devastating is that these deaths are preventable,” says Dr. Paxton Bach, co-medical director at the BC Centre on Substance Use. “We’re seeing unprecedented levels of drug toxicity combined with an inadequate and fragmented response system.”

The lethal unpredictability of today’s unregulated drug supply is driven by synthetic opioids like fentanyl, detected in 86% of deaths this year. Even more alarming is the presence of benzodiazepines in nearly half of samples tested – a dangerous combination that increases overdose risk and complicates response efforts since naloxone doesn’t reverse “benzo” effects.

Walking through Victoria’s North Park neighborhood last week, I met Darren, who lost his brother to a toxic drug poisoning in February. “The stuff on the streets now – it’s nothing like what was around even five years ago,” he explained, adjusting his baseball cap. “My brother thought he was getting one thing. What he got killed him in minutes.”

The crisis continues to affect people from all walks of life, though certain demographics bear a disproportionate burden. Men represent nearly 80% of deaths, with those aged 30-59 most affected. And while the crisis touches every community, the statistics reveal that First Nations people in BC die at 5.7 times the rate of non-Indigenous residents.

“This crisis reflects the ongoing impacts of colonization, intergenerational trauma, and systemic barriers to culturally safe care,” explains Darlene Beck, director of health programs at the First Nations Health Authority. “True healing requires Indigenous-led approaches that address both immediate harms and underlying causes.”

The provincial government has expanded some harm reduction services, including supervised consumption sites and access to naloxone. In March, BC expanded its prescribed safer supply program, allowing more healthcare providers to prescribe pharmaceutical alternatives to toxic street drugs.

Critics argue these measures, while important, remain insufficient in scale and accessibility. Rural and remote communities, in particular, lack many of the resources available in urban centers.

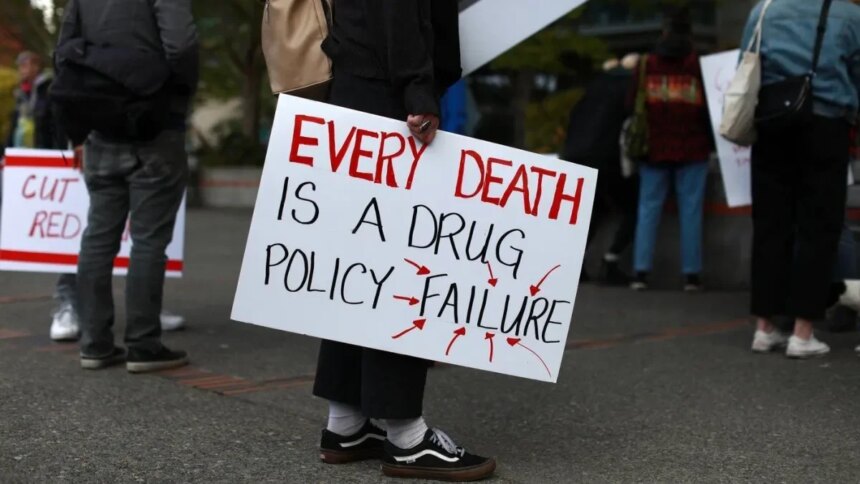

“When we talk about a toxic drug crisis, we need to emphasize that ‘toxic’ refers to the supply, not the people,” says Guy Felicella, a peer clinical advisor who experienced addiction for over two decades before finding recovery. “The stigma around substance use remains one of our biggest barriers to implementing effective solutions.”

Experts point to several evidence-based approaches that could reduce deaths, including expanded safe supply programs, decriminalization of personal possession, more treatment options, and addressing root causes like trauma, poverty, and housing insecurity.

Walking back to my car after visiting the memorial wall, I noticed a small group gathered in a nearby park. They were holding a remembrance ceremony for someone recently lost. A woman in a red jacket placed flowers on a small memorial. A man played a soft melody on a wooden flute. Community in grief, community in action.

This pattern repeats across British Columbia – loss, mourning, and a determined push for change. As another month of devastating statistics reminds us, the toxic drug crisis continues to demand our attention, our compassion, and most urgently, our action.

The monthly report from the BC Coroners Service isn’t just data. It’s a call to recognize that every number represents someone’s child, parent, sibling, or friend. And a reminder that tomorrow’s statistics aren’t yet written.