In the shadow of diplomatic buildings in Washington and Brussels, a new trade war is brewing. I’ve spent the past week talking with trade representatives, economists, and business owners watching with apprehension as President-elect Donald Trump ratchets up tariff threats against longtime U.S. allies.

“We’re looking at complete reorganization of global trade flows,” said Miguel Sanchez, a Mexican trade official I met at a closed-door economic forum in D.C. yesterday. His usually measured diplomatic tone had given way to barely concealed alarm. “These aren’t just numbers on paper. These are real jobs, real communities that will feel this first.”

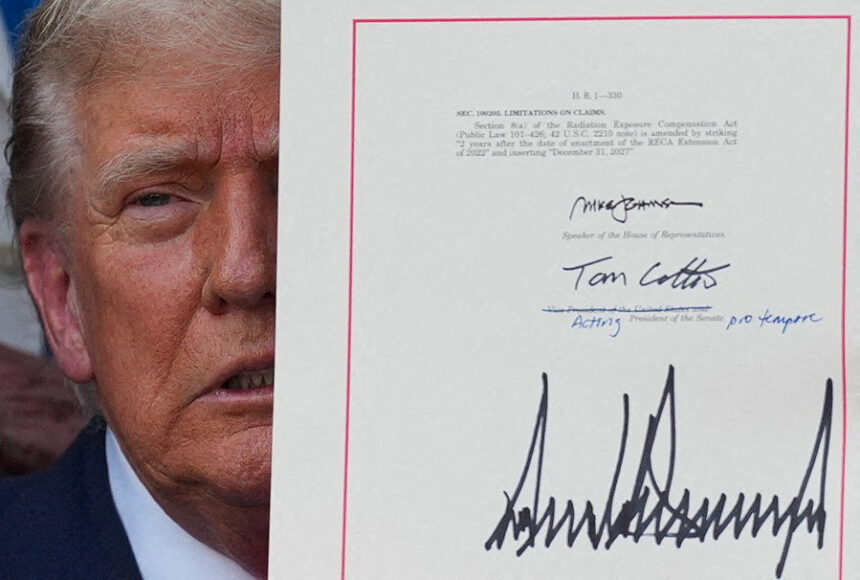

Trump’s recent announcement threatening 30-35% tariffs on goods from Canada, Mexico, and the European Union marks a dramatic escalation from his previous administration’s trade policies. Sources close to the transition team indicate these tariffs could take effect within days of his January inauguration, bypassing the typical study periods and impact assessments that usually precede such significant trade actions.

What makes this round of tariff threats particularly destabilizing is their scope. Unlike targeted tariffs on specific industries, these broad-based taxes would impact nearly every sector of trade between the U.S. and its three largest trading partners. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, combined trade with these partners totaled over $1.7 trillion last year.

Walking through a Wisconsin dairy farm last month for another story, I witnessed the complex interdependence firsthand. “We ship to processing plants that sell to Mexico, while using equipment with parts from Germany,” the farm owner told me. “Where exactly in that chain are the foreign goods that need taxing?”

The European Commission hasn’t waited to respond. In Brussels, officials have already drafted retaliatory measures targeting politically sensitive American exports. An EU trade representative shared on background that their list strategically includes agricultural products from swing states and luxury goods from states with significant electoral importance.

“We learned from 2018,” the representative told me, referencing the previous Trump administration’s steel and aluminum tariffs. “This time, our response will be immediate and precisely calibrated.”

Canada and Mexico appear to be coordinating their responses as well. During a call with Canadian Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland yesterday, she emphasized that while they prefer dialogue, they’ve prepared sector-by-sector countermeasures. “We won’t hesitate to defend Canadian workers, just as we did successfully before,” she stated.

The economic stakes are enormous. The Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates these tariffs could cost American consumers an additional $78 billion annually through higher prices. Their analysis suggests up to 300,000 American jobs could be lost in manufacturing and agriculture as retaliatory tariffs cut access to foreign markets.

But beyond the economic implications lie deeper questions about the rules-based international order. Three separate WTO officials I’ve spoken with in recent weeks expressed concern that these tariffs would likely violate multiple trade agreements, including the USMCA that replaced NAFTA during Trump’s first term.

“The system only works when major economies follow the rules they helped create,” said one senior WTO official who requested anonymity given the sensitivity of the situation. “Unilateral actions of this magnitude threaten the entire framework.”

In border communities from Laredo to Detroit, uncertainty reigns. Standing at the Ambassador Bridge crossing between Detroit and Windsor last week, I watched the endless stream of trucks carrying auto parts between the deeply integrated U.S. and Canadian manufacturing sectors. Local business owners described how the just-in-time supply chains could collapse under the weight of new tariffs.

“You can’t just flip a switch and ‘bring production back,'” explained Carlos Gutierrez, former U.S. Secretary of Commerce under President George W. Bush, when I spoke with him by phone. “These supply chains took decades to build. Disrupting them creates cascading problems nobody can fully predict.”

The White House has responded cautiously to Trump’s threats, emphasizing that President Biden remains committed to rules-based trade while his administration evaluates response options during the transition period.

Perhaps most concerning is how quickly this dispute could spiral beyond trade. During my conversation with a senior NATO official in Brussels, they noted the alliance’s cohesion depends partly on economic cooperation. “Security partnerships become strained when economic relationships deteriorate,” they said. “These aren’t separate domains anymore.”

As I prepare to head to Mexico City next week to cover the government’s emergency economic planning sessions, the question isn’t just how high the tariff barriers might rise, but whether decades of economic integration can withstand renewed nationalism. The intricate web of trade relationships that has defined North American and transatlantic economic cooperation for generations now hangs in the balance, with workers and consumers on all sides waiting to learn what comes next.